For millions of people around the U.S., particularly women, minorities and members of marginalized populations, the last few months have felt like a descent into darkness. Every day we learn of fresh horrors in the news, from a rise in hate crimes, to an ever-growing list of punishing legislation, to the latest presidential tweet. With so many issues suddenly in need of highlighting, Jessica and I didn’t know where to start. And then it hit us: light a candle amid all that darkness.

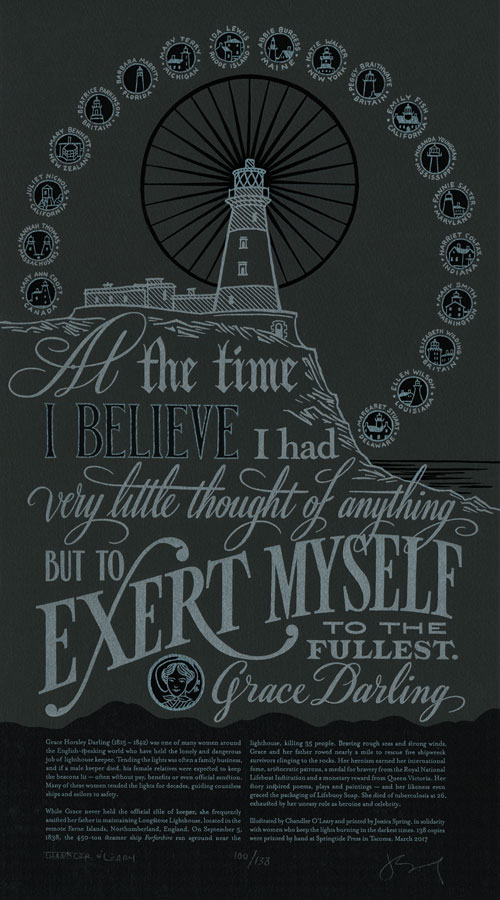

The resistance movement of which we now consider ourselves members feels like a collection of beacons shining in the night. So we turned to those who literally kept a light on to protect those in the dark: the many women lighthouse keepers of the last century or more. We’ve highlighted twenty of these brave keepers in our new Dead Feminists broadside, and centered a quote by Grace Darling:

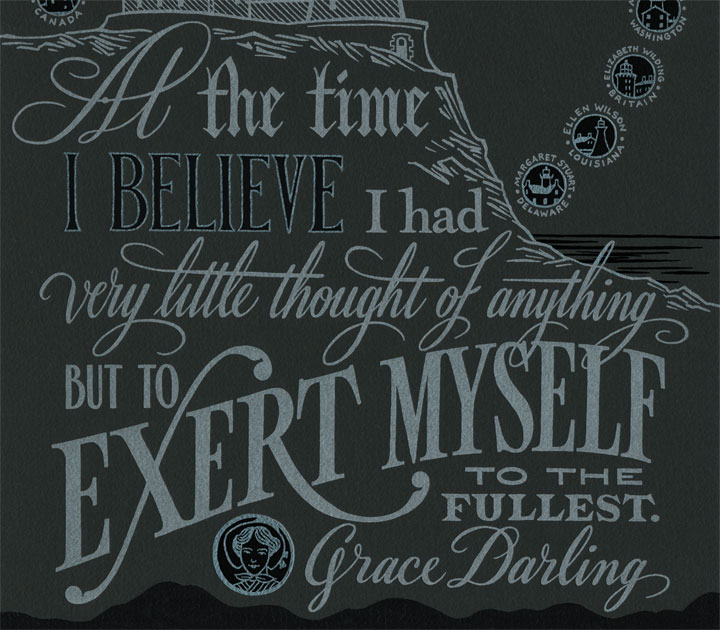

“At the time I believe I had very little thought of anything but to exert myself to the fullest.”

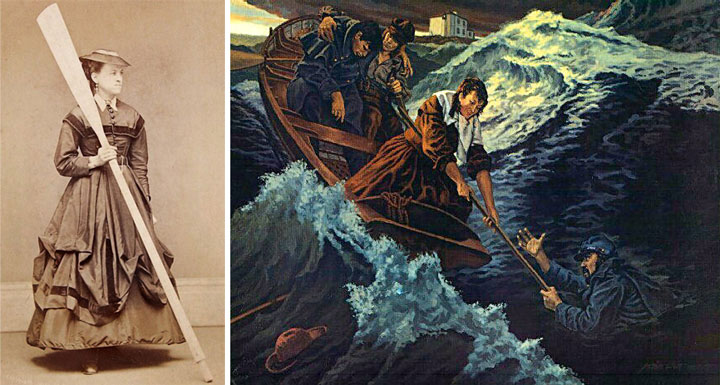

Grace Darling is just one of countless women who have—by choice or necessity—spent their lives out on lonely rocks and islands, keeping a light burning in the dark to protect seafarers from running afoul of the shore. We chose to focus on Grace because her life included a unique act of heroism.

On the night of September 5, 1838, Grace and her father discovered that a ship had wrecked on the shoals near their lighthouse in the north of England. The pair rowed out to find several survivors clinging to the rocks—while Grace steadied the rowboat, her father managed to save five people by hauling them aboard. After the incident, word quickly spread about the disaster and subsequent rescue, and seemingly overnight, Grace became a celebrity and national heroine.

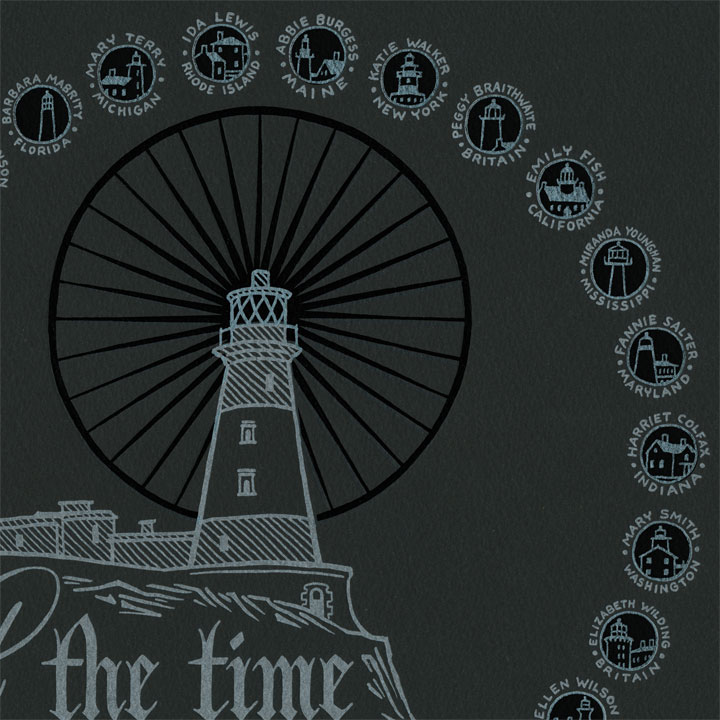

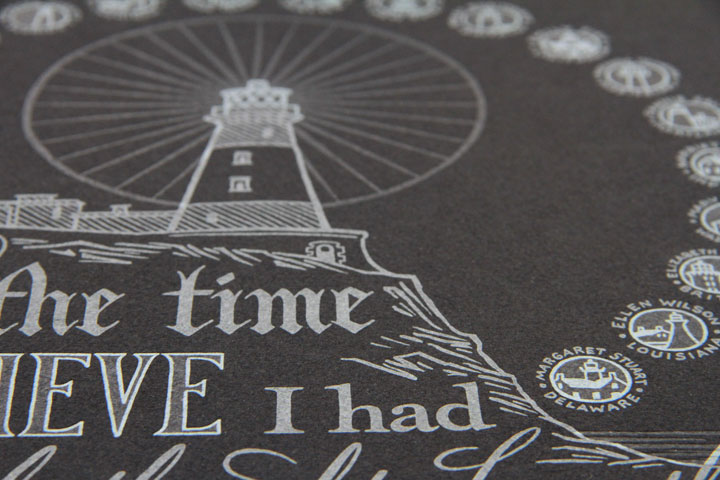

Grace gave us a great quote, but we also wanted to include as many other women lighthouse keepers as we could, because together their lights form a glowing constellation of hope, bravery and selflessness.

There was Ida Lewis, Grace’s American counterpart who also rescued her fair share of shipwrecked sailors—she is credited with saving 18 lives from her Rhode Island post. When criticized for the unladylike activity of “manning” a heavy rowboat, Ida quipped, “None – but a donkey, would consider it ‘un-feminine’, to save lives.”

Fannie Salter devoted 45 years of her life to Maryland’s Turkey Point Light—and, yes, even raised turkeys there.

And then there’s Emily Fish, who wo-manned what is now the oldest continuously-operating lighthouse on the West Coast. Or Katie Walker, who first helped her husband keep Sandy Hook Light in New Jersey, and then after his death tended Robbins Reef Light Station off the coast of Staten Island. His last words to her were “Mind the light, Katie.”

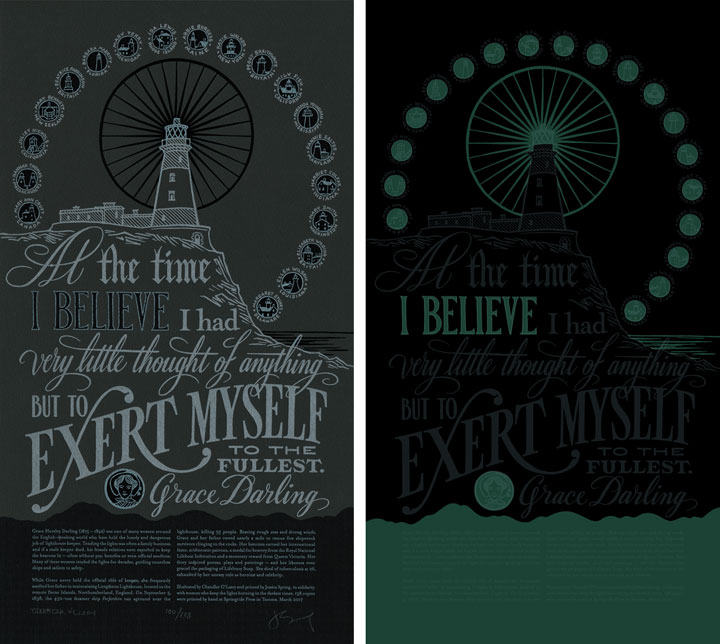

It’s stories like these that help keep us afloat these days—and we hope they’ll be a lifeline for you, too. To inject even more brightness into the dark, we printed our second black-paper design using bright seafoam-and-silver metallic ink. And there’s more—one last secret in the deep. Do you see that black-on-black varnish above?

That varnish catches the light and shines in a whole different way from the metallic silver.

And that’s because it’s not varnish at all—

—but a special formula of glow-in-the-dark ink. Charge up the ink with a bright light first (either daylight or a bright bulb), and you’ll see the design burn with a subtle glowing luminescence like a green flash in darkness.

To help the next generation of courageous girls become seafarers and mariners, we are donating a portion of our proceeds to the Girls Boat Project. A joint program of the Northwest Maritime Center and the Port Townsend (Washington) Public School District, the Girls Boat Project teaches the maritime trades to girls aged 12-18.

Update: Sold out. Reproduction postcard is now available.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

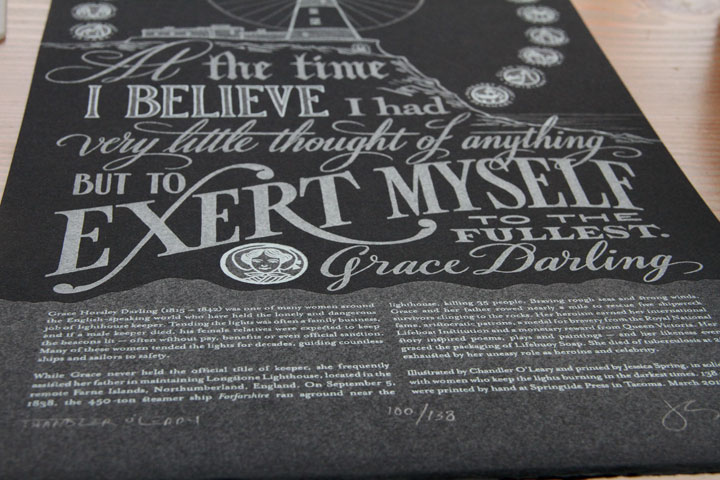

Save Our Ship: No. 25 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 138

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Grace Horsley Darling (1815 – 1842) was one of many women around the English-speaking world who have held the lonely and dangerous job of lighthouse keeper. Tending the lights was often a family business, and if a male keeper died, his female relatives were expected to keep the beacons lit — often without pay, benefits or even official sanction. Many of these women tended the lights for decades, guiding countless ships and sailors to safety.

While Grace never held the official title of keeper, she frequently assisted her father in maintaining Longstone Lighthouse, located in the remote Farne Islands, Northumberland, England. On September 5, 1838, the 450-ton steamer ship _Forfarshire_ ran aground near the lighthouse, killing 35 people. Braving rough seas and strong winds, Grace and her father rowed nearly a mile to rescue five shipwreck survivors clinging to the rocks. Her heroism earned her international fame, aristocratic patrons, a medal for bravery from the Royal National Lifeboat Institution and a monetary reward from Queen Victoria. Her story inspired poems, plays and paintings — and her likeness even graced the packaging of Lifebuoy Soap. She died of tuberculosis at 26, exhausted by her uneasy role as heroine and celebrity.

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, in solidarity with women who keep the lights burning in the darkest times.