We’ve all been inundated these last months with news headlines about inflation, “quiet quitting,” and an absolutely religious devotion to the economy. Meanwhile, reality contradicts the sensationalism. Oil companies and grocery monopolies see record profits while we pay dearly for the essentials. Employees push back on the idea that they must sacrifice all to employers that see them as replaceable cogs, and some turn to an age-old organized labor tactic called “work to rule.” And the pandemic inspired our leaders to prioritize the stock market over the very lives of workers, families, the vulnerable, and the marginalized. Billionaires became even richer during the pandemic, fattening up on the fruits of our labor while the rest of us fight over the crumbs. Fed up with it all, we turned to the patron saint of American laborers, Frances Perkins, and found a fitting quote that doesn’t mention labor at all:

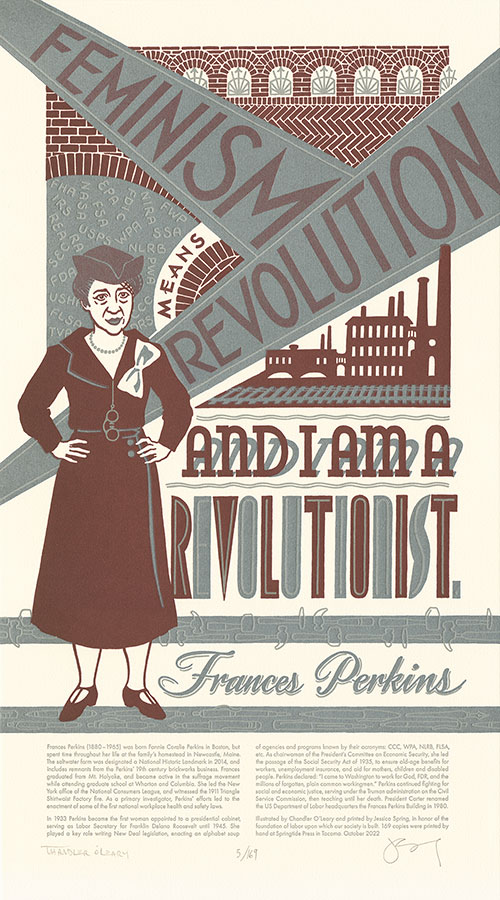

Feminism means revolution and I am a revolutionist.

Before we committed it to paper, we sat with that quote for a while. After all, in fourteen years of producing our Dead Feminists series, we have intentionally steered clear of using the term feminism, letting the words and deeds of our historical women mark them as feminists instead. But given the current obsession with gender displayed by politicians, the courts, the media, and society at large—overturning Roe v. Wade, a slew of anti-trans legislation and violence, and vast numbers of women and caregivers of all genders leaving the workforce during the pandemic—it felt like now was the time to drop the F-bomb. After all, if the powerful feel such a need to exert control over us, then feminism must be an incendiary force. And just like society itself, the feminist revolution is built, brick by brick, on a foundation of work.

Frances Perkins might seem an unlikely icon of the revolution—she wasn’t a celebrity, or a sex symbol, or a martyr. But it’s impossible to understate how much we owe to her work, her many years sitting at a desk and drafting documents. We have Perkins to thank for the minimum wage, Social Security, work-hour limitations, workplace safety regulations, employee injury compensation, unemployment benefits, anti-child-labor laws, disability income, and more. It was her pen that sketched out our social safety net, her papers that formed the pillars of our labor laws, her cornerstone that supports our firewall of financial protections. And it was labor—and labor tragedies—that inspired her deeds.

On March 25, 1911, the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory, a garment sweatshop located on the top three floors of a ten-story building near Washington Park in Manhattan, caught fire. Using a then-common practice to prevent theft and unauthorized employee breaks, the exit doors leading to two of the stairwells were locked. (Some historians have asserted that the doors were also locked to prevent union organizers from entering the factory floor.) The foreman, who had the key, escaped as soon as the fire broke out and left the workers behind. Within three minutes, the only unlocked stairwell was inaccessible. Fire ladders only reached the seventh floor, and the two working freight elevators couldn’t keep up with the elevator operators’ brave rescue attempts. The fire killed 146 garment workers—including 123 women and girls, most of whom were recent immigrants of Italian or Jewish heritage. Sixty-two of those killed died by jumping out of a window or falling from the single flimsy fire escape, which collapsed.

Since it was a Saturday, there were many eyewitnesses on the street below, including a young Frances Perkins, who at the time ran the New York office of the National Consumers League. City officials formed the Committee on Public Safety in the aftermath, and appointed Perkins its head. She conducted investigations and enlisted the help of powerful lobby groups like Tammany Hall to pressure the state legislature to enact reforms. Their joint efforts led to the creation of a commission to investigate factory conditions, and by 1913 the legislature had passed 60 new labor laws, making New York State the most progressive in the union for worker’s rights. These laws shortened the work week, mandated building fireproofing, alarm systems and emergency exits, guaranteed better access to food and toilet facilities for workers, and limited work hours for women and children.

Just over 20 years after the disaster, newly-elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed Perkins to his cabinet as Secretary of Labor. When she accepted the position, she presented FDR with a long list of social programs that she wanted to fight for—when he agreed to back her agenda, she replied, “Nothing like this has ever been done in the United States before. You know that, don’t you?” What followed, starting in the first hundred days of FDR’s presidency, was the establishment of approximately 69 New Deal agencies and programs that the press labeled with the derogatory nickname of “Alphabet Soup.” These initiatives, known by their acronyms, became FDR’s biggest accomplishment and his legacy—yet few know of the women’s work behind them. Perkins did the groundwork and legislative legwork, and many of the programs were inspired by Eleanor Roosevelt’s efforts before she became First Lady. In 1927 she co-founded Val-Kill Industries, an artisan factory and collective to support traditional craftspeople, in upstate New York. The program became a prototype for the New Deal program as a whole, and provided the framework for some of Perkins’ initiatives.

Each one of the New Deal programs was downright revolutionary, and even now they remain some of the few barriers between prosperity and poverty for many Americans. Yet today we take them for granted, even as conservative politicians try their hardest to dismantle them. Many voters are still more worried about the economy than democracy or even bodily autonomy, while sitting GOP Senator Mike Lee was caught on camera saying it would be his “objective to phase out Social Security” and that he’ll “pull it up by its roots.” These shenanigans are not a new deal: in her time, Frances Perkins was accused of being a communist, and in 1939 she was the first Cabinet member Congress ever attempted to impeach. Though the proceedings were dropped due to lack of evidence, and Perkins went on to serve for the full 12 years of his presidential term, FDR never spoke in her defense. (This is an excellent reminder that we need to speak up for ourselves: your vote on November 8 is essential to push back against the efforts—in Congress and in the courts—to take away our rights.)

Being left high and dry by FDR couldn’t have surprised Perkins, whose professional persona was constructed around neutralizing men’s hostility toward her. She took notes on her male colleagues and filed them in a red envelope labeled “Notes on the Male Mind.” She wore a daily uniform of plain dark suits, zero makeup and smart hats. (She especially liked tricornered ones—a bit of subtle revolutionary flair?) This matronly look had a purpose: she believed that men, particularly in politics, only accepted women colleagues who reminded them of their mothers. She said, “I tried to have as much of a mask as possible. I wanted to give the impression of being a quiet, orderly woman who didn’t buzz-buzz all the time… I knew that a lady interposing an idea into men’s conversation is very unwelcome. I just proceeded on the theory that this was a gentleman’s conversation on the porch of a golf club perhaps. You didn’t butt in with bright ideas.” Instead, she saved those bright ideas and wrote them into federal policy.

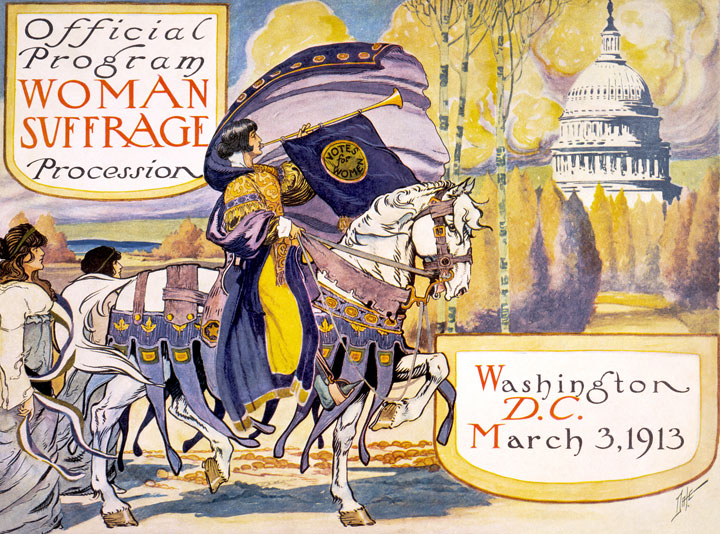

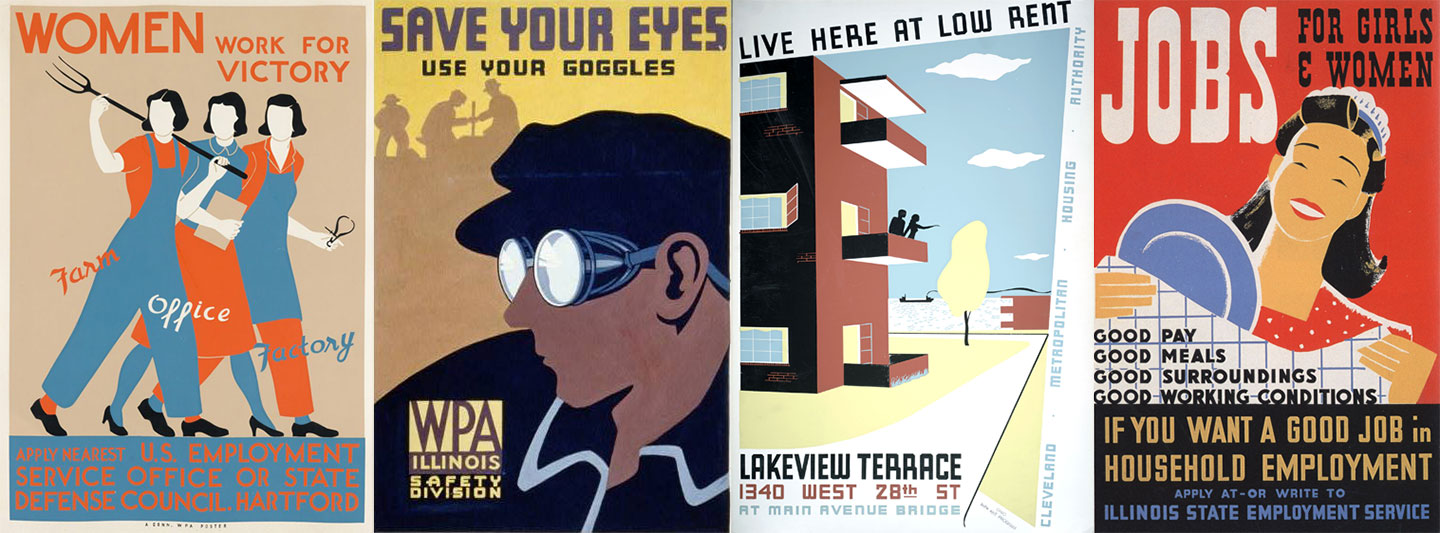

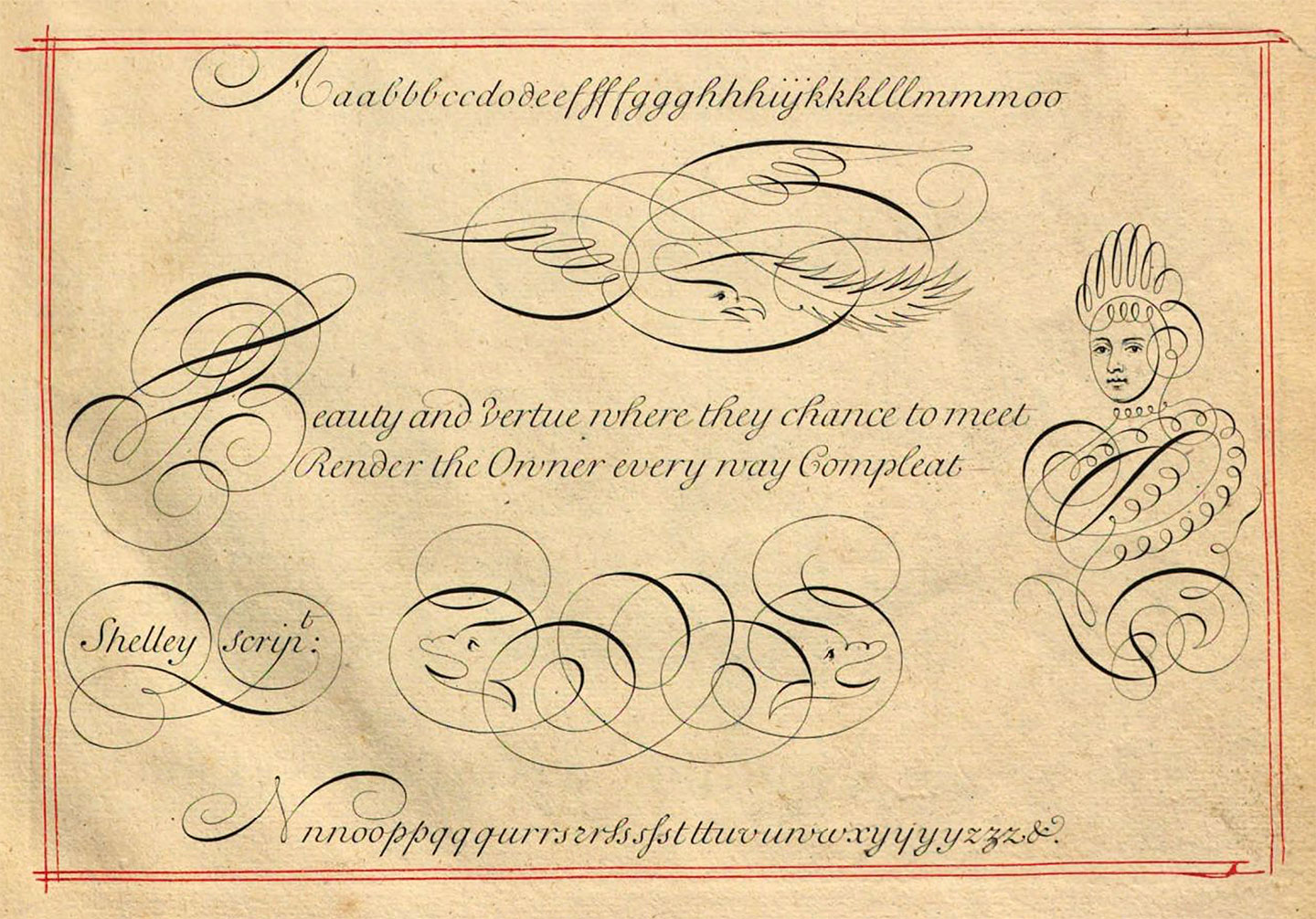

In our latest broadside, Devotional Labor, we reference both the social scaffolding Perkins built—with a nod to her family’s brickyard business—and the revolutionary nature of her work. We used metallic inks throughout for an industrial feel and to enhance the print’s bold, graphic shapes. The design and 1930s color scheme is an homage to the famous posters of the Works Progress Administration (WPA), which, like Val-Kill Industries before it, put unemployed artists back to work during the Depression.

Books (Please)! In All Branches of Knowledge, by Aleksandr Rodchenko, 1924

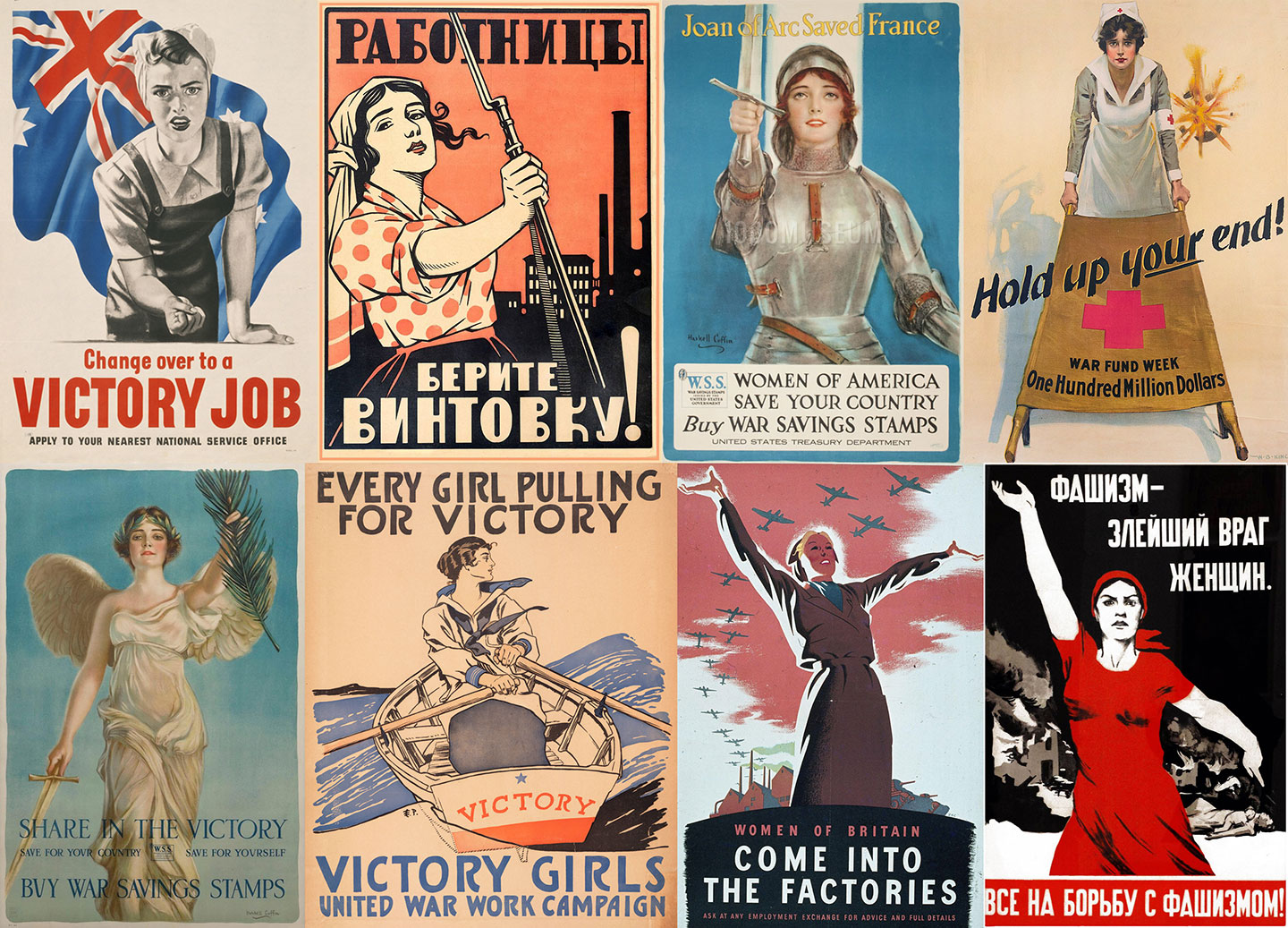

Many of those WPA poster artists were in turn influenced by revolutionary posters and other political propaganda from around the world (including, a bit ironically, the Soviet communists).

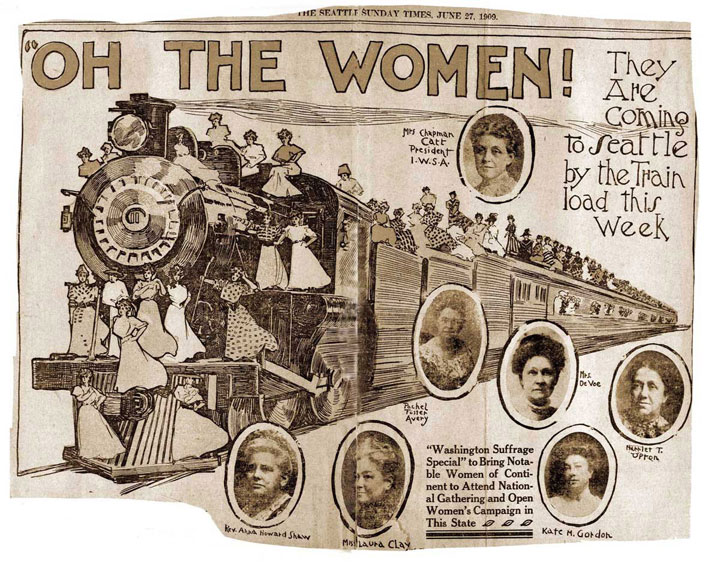

Often these historic propaganda posters have a whiff of religion about them, particularly those that feature a central feminine figure. Though some are depicted for their attractiveness, many of these are presented as saints, selfless mother archetypes, or even goddesses.

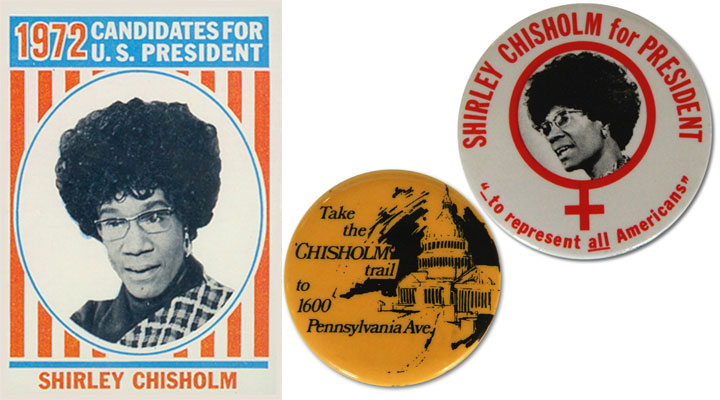

Posters from before 1950 with this theme all center white women, but later propaganda from around the world often followed the same playbook: women as warrior-mothers, farmer-goddesses, standard-bearers. Notably, many of these displayed anti-American sentiment (see some of the Vietnamese posters above). And many were created by sympathetic artists in allied countries—like the Angola piece made by a Cuban artist, or the Chinese poster in the lower right that says “American imperialism, get out of Africa.”

Some of the most interesting of these depict women who aren’t sexy or divine, but sturdy, strong, common, “everywoman” laborers. Everyone has seen Rosie the Riveter, but these posters also celebrated careworn farm matrons and burly industrial mavens. By alluding to this pantheon of heroines in our broadside, we also wanted to reference the other meanings of the word “labor.” There’s the labor of childbirth and rearing—the work of literally creating the next generation of workers—and the labor pains of birthing a movement, of course. But we also acknowledge the unpaid, heavily-gendered work that also underpins our society: caregiving, household economics, and even emotional labor.

Perkins herself was devoutly religious: raised Congregationalist (the modern church that evolved from the Puritans who settled New England) by a conservative family who was horrified by her early suffragist leanings, she joined an Anglo-Catholic church at age 25 and adopted the name of Frances upon her confirmation. Later she brought her Anglo-Catholic sensibilities to her membership in the Episcopal church. So we’ve added a dash of religious iconography to our letterpress devotional. Perkins’ portrait is adorned with a “halo” of alphabet agency acronyms on a blue ground that references religious icons and early-church mosaics. She stands on a silver layer of mighty pens, which form the foundation for the pattern of hammers that support the brick-and-mortar design above.

To help bolster women and feminist workers in every kind of labor, we are donating a portion of our proceeds to 9to5, a non-profit that fights for workers on many fronts: equal pay, affordable housing, paid sick and family leave, workplace sexual harassment, raising the minimum wage, and more. We are making a second donation to the Frances Perkins Center to help support the historic Perkins Homestead and preserve Perkins’ legacy. We are supporting both organizations via Action Grants from the Dead Feminists Fund.

Purchase your copy in the shop!

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Devotional Labor: No. 33 in the Dead Feminists series

Edition size: 169

Poster size: 10 x 18 inches

Printed on an antique Vandercook Universal One press, on archival, 100% rag (cotton) paper. Each piece is numbered and signed by both artists.

Colophon reads:

Frances Perkins (1880 – 1965) was born Fannie Coralie Perkins in Boston, but spent time throughout her life at the family’s homestead in Newcastle, Maine. The saltwater farm was designated a National Historic Landmark in 2014, and includes remnants from the Perkins’ 19th century brickworks business. Frances graduated from Mt. Holyoke, and became active in the suffrage movement while attending graduate school at Wharton and Columbia. She led the New York office of the National Consumers League, and witnessed the 1911 Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. As a primary investigator, Perkins’ efforts led to the enactment of some of the first national workplace health and safety laws.

In 1933 Perkins became the first woman appointed to a presidential cabinet, serving as Labor Secretary for Franklin Delano Roosevelt until 1945. She played a key role writing New Deal legislation, enacting an alphabet soup of agencies and programs known by their acronyms: CCC, WPA, NLRB, FLSA, etc. As chairwoman of the President’s Committee on Economic Security, she led the passage of the Social Security Act of 1935, to ensure old-age benefits for workers, unemployment insurance, and aid for mothers, children and disabled people. Perkins declared: “I came to Washington to work for God, FDR, and the millions of forgotten, plain common workingmen.” Perkins continued fighting for social and economic justice, serving under the Truman administration on the Civil Service Commission, then teaching until her death. President Carter renamed the US Department of Labor headquarters the Frances Perkins Building in 1980.

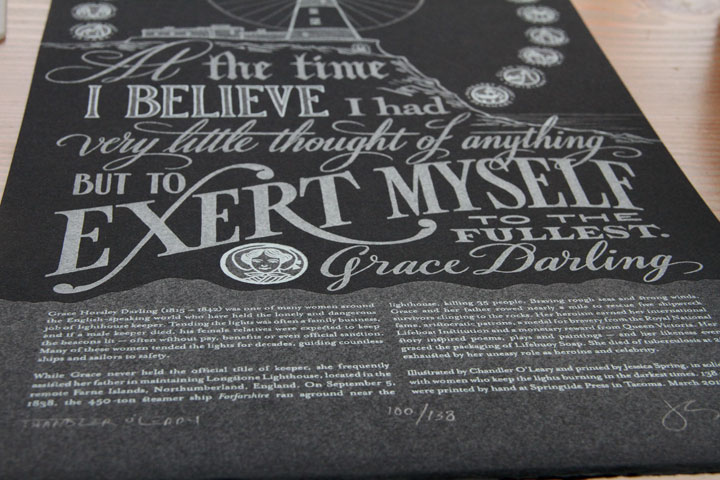

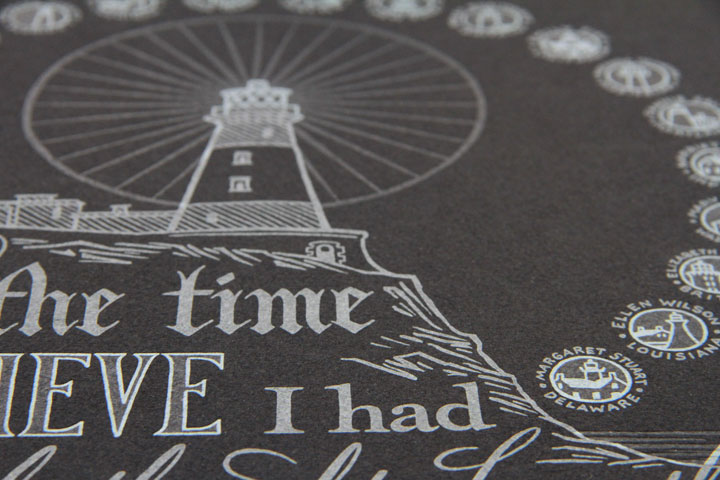

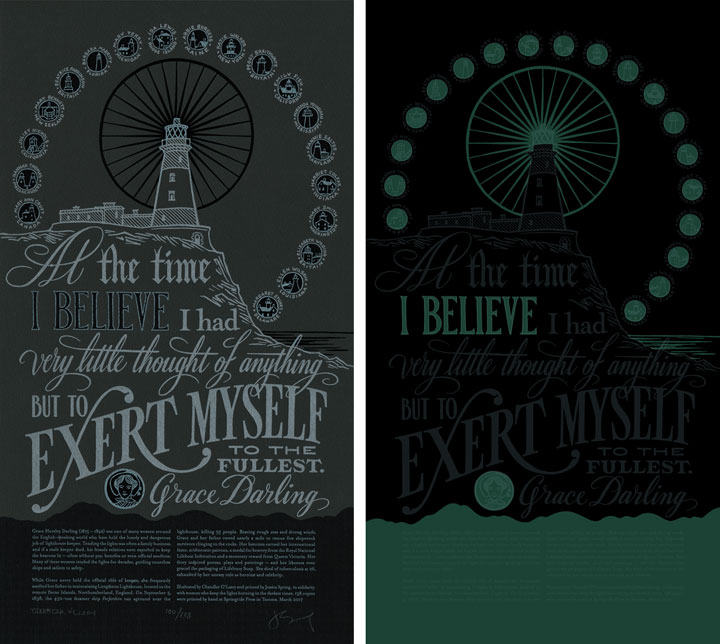

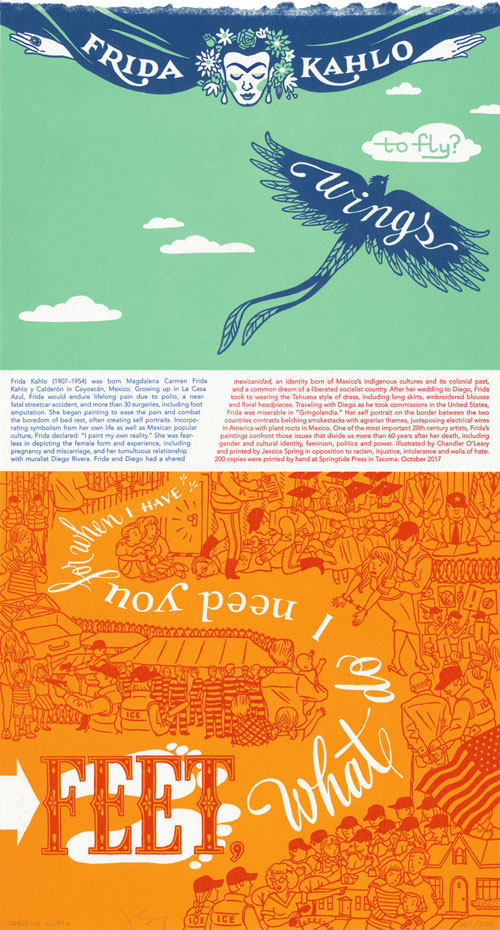

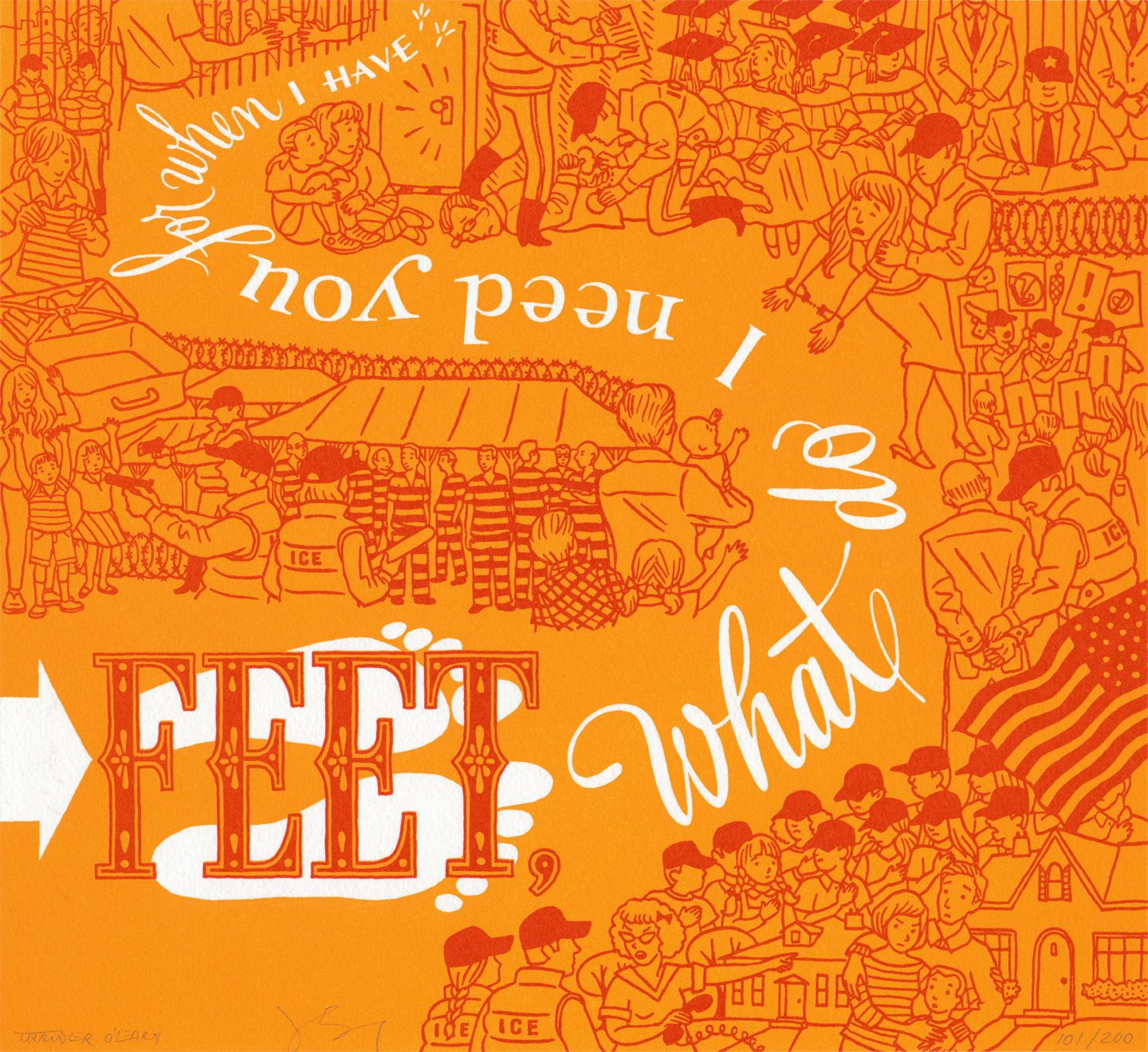

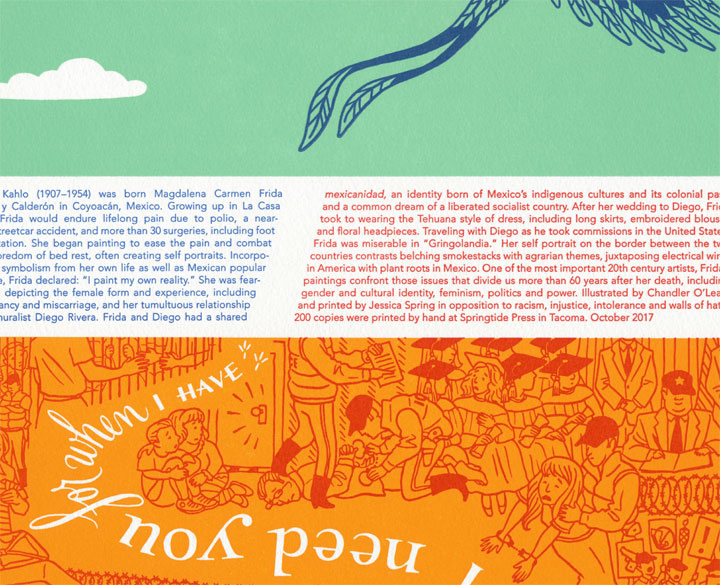

Illustrated by Chandler O’Leary and printed by Jessica Spring, in honor of the foundation of labor upon which our society is built. 169 copies were printed by hand at Springtide Press in Tacoma.

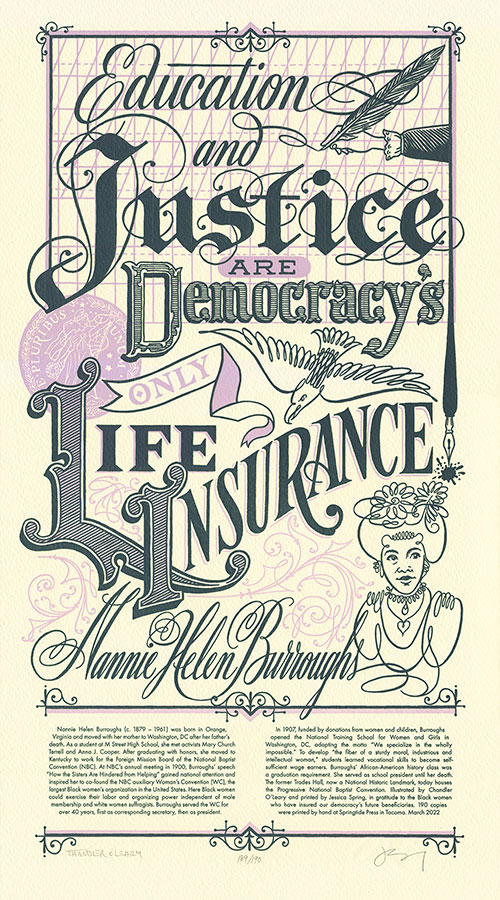

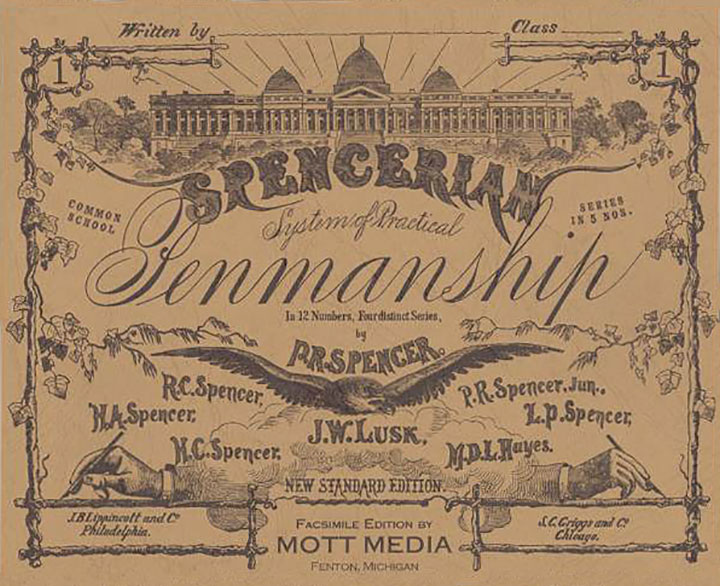

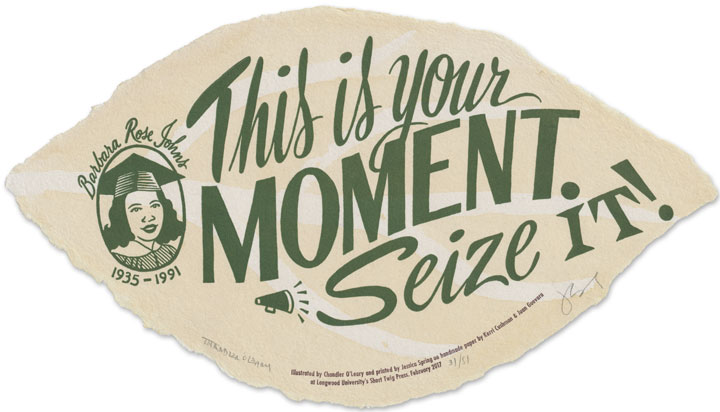

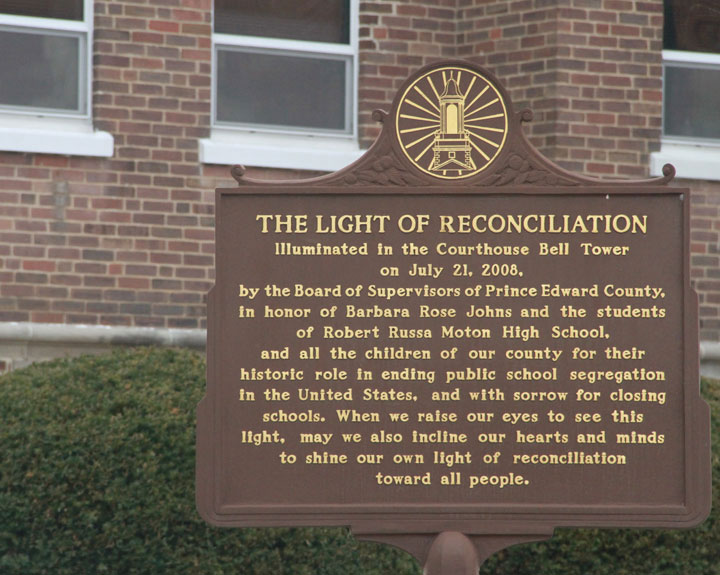

As a result of the Brown decision, in 1959 the Board of Supervisors refused to appropriate any funds at all for the County School Board. From 1959 to 1964 Prince Edward County closed their public schools to avoid integration. While many white children attended segregated private schools, black children had to go elsewhere, attend makeshift schools, or forego years of formal education. In 1964, The Supreme Court in Griffin v. Prince Edward ordered schools to reopen, declaring “the time for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out.”

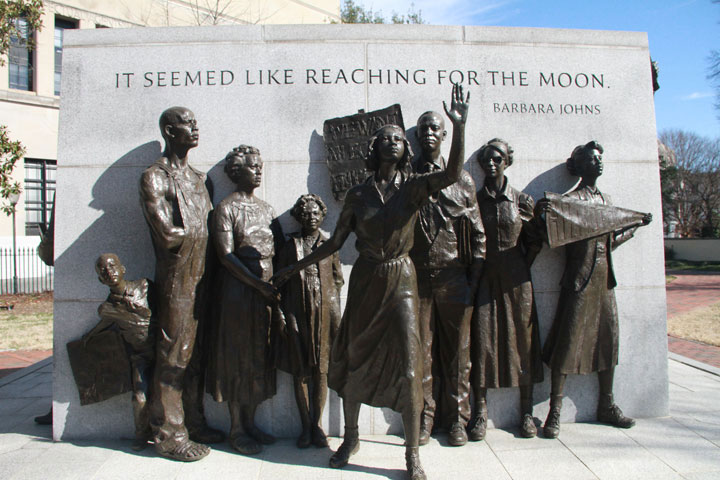

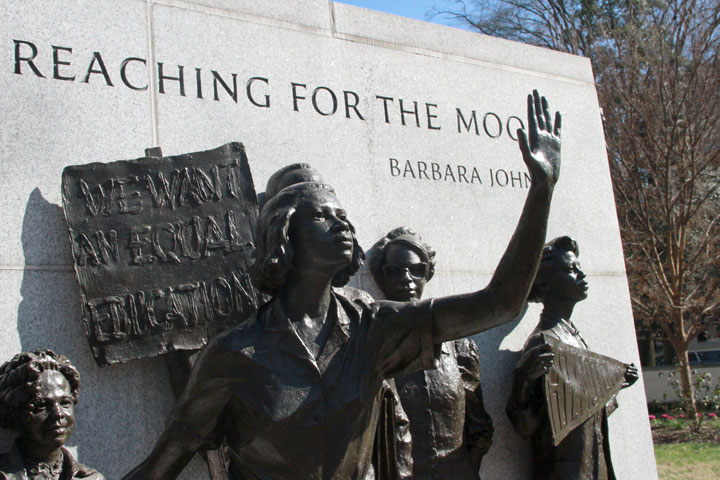

As a result of the Brown decision, in 1959 the Board of Supervisors refused to appropriate any funds at all for the County School Board. From 1959 to 1964 Prince Edward County closed their public schools to avoid integration. While many white children attended segregated private schools, black children had to go elsewhere, attend makeshift schools, or forego years of formal education. In 1964, The Supreme Court in Griffin v. Prince Edward ordered schools to reopen, declaring “the time for mere ‘deliberate speed’ has run out.” The Virginia Civil Rights Memorial in Richmond honors Barbara and the striking students.

The Virginia Civil Rights Memorial in Richmond honors Barbara and the striking students.

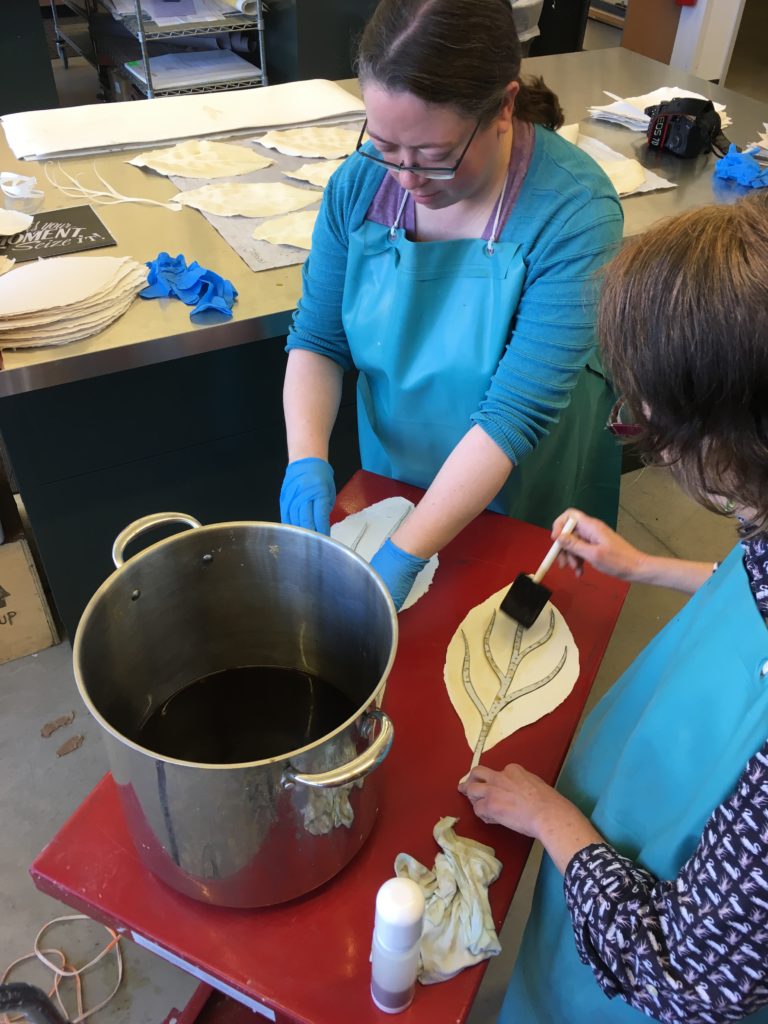

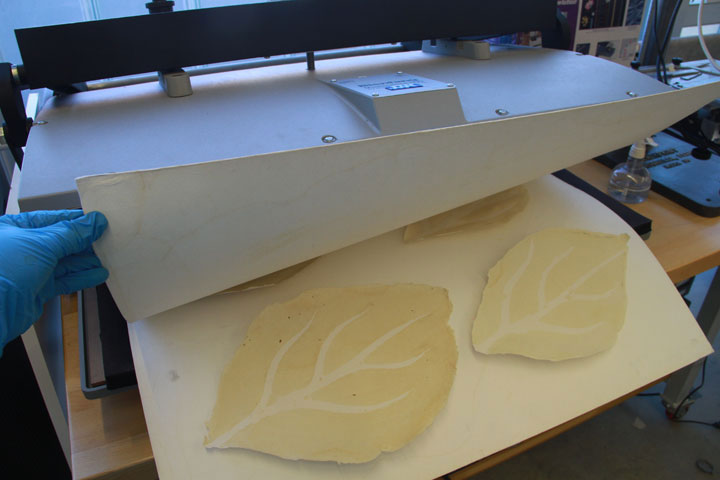

The shaped leaf was best handled through the presses by carefully mounting with painter’s tape on a carrier sheet.

The shaped leaf was best handled through the presses by carefully mounting with painter’s tape on a carrier sheet.

We completely enjoyed the opportunity to learn more about Farmville, papermaking, the Moton Museum, and of course, Barbara Rose Johns, as we share her story. We hope “A Leaf From Her Book” honors her bravery as a young woman, but also her continued commitment to education, as shown through her work as a librarian until the end of her life in 1991.

We completely enjoyed the opportunity to learn more about Farmville, papermaking, the Moton Museum, and of course, Barbara Rose Johns, as we share her story. We hope “A Leaf From Her Book” honors her bravery as a young woman, but also her continued commitment to education, as shown through her work as a librarian until the end of her life in 1991. Very special thanks to Longwood Professors Kerri Cushman and Larissa Fergeson–collaborators, teachers and hosts–for seizing the moment with us.

Very special thanks to Longwood Professors Kerri Cushman and Larissa Fergeson–collaborators, teachers and hosts–for seizing the moment with us.